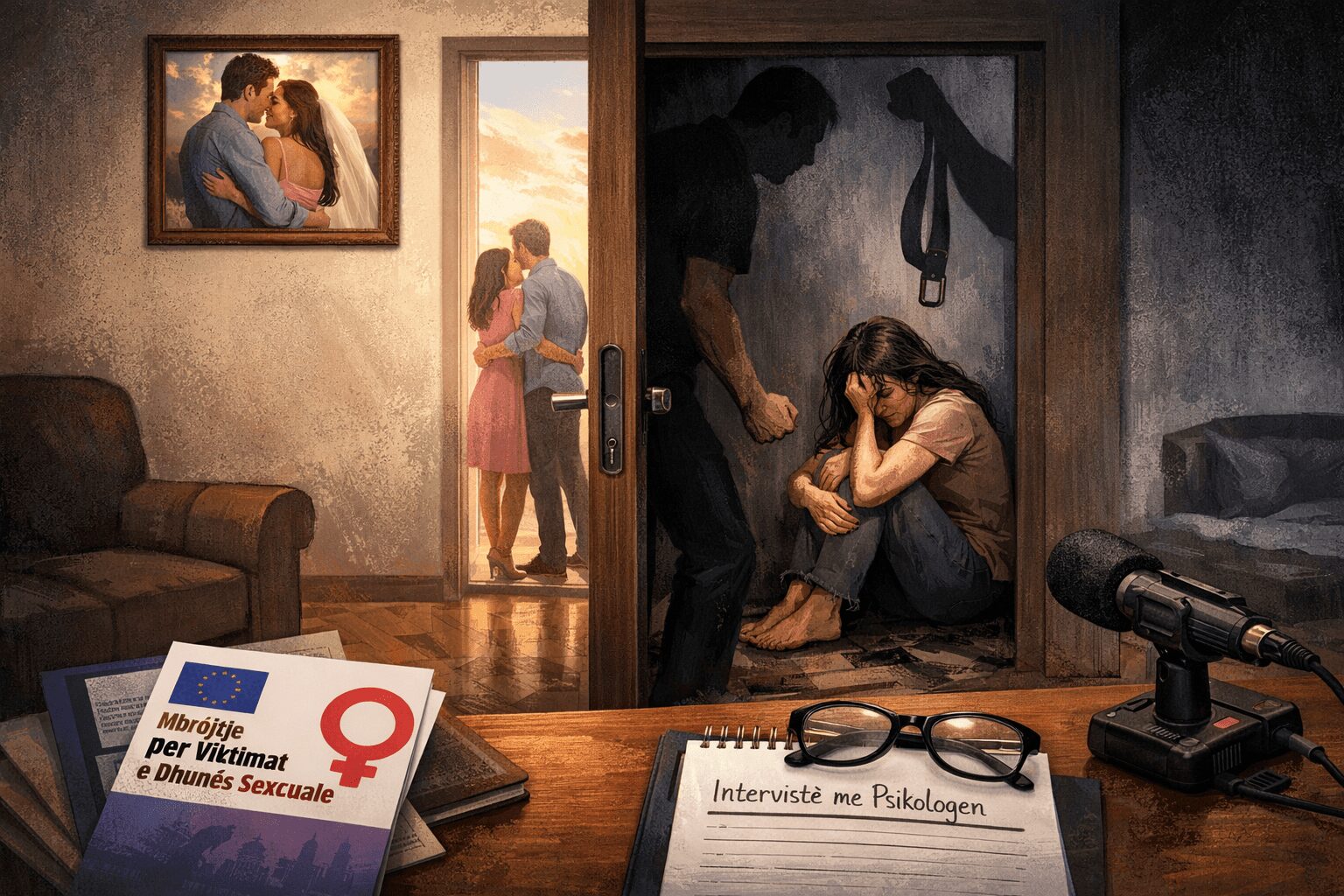

While various promotional materials in orange were being prepared, the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence were preceded by yet another murder of a woman. Another femicide was added to an ever-growing list of names, stories, and ignored warnings. This fact is not merely tragic; it is a symptom of a deep social as well as institutional crisis.

Femicide is not an isolated act of violence. Before a woman is killed, she is usually being threatened, beaten, and controlled. Before the murder occurs, there are warning signs. And before she is silenced forever, society and institutions fall silent many times.

The increase in cases of femicide in North Macedonia cannot be understood outside the context of everyday gender-based violence. Often, after a murder, public discourse focuses on the final moment: what happened that day, what “provoked” the perpetrator, why he “went that far.” This focus obscures the most important question: what happened before, and why did no one stop it?

Silence learned in the family and normalized by society

The politics of silence begin early, within the family, where violence is often relativized and rationalized before it is even named. Children grow up hearing that problems should be “resolved within four walls,” and that patience is a virtue. Girls are taught to adapt, to remain silent, and to carry the burden of family harmony, even when it is built on fear and pain. Boys, meanwhile, are socialized into the idea that male authority is natural, unquestionable, and protected by collective silence.

These lessons create the ground on which violence is perceived as part of everyday life rather than as a violation of fundamental human rights. Silence is transformed into a moral virtue, while speaking about violence is seen as betrayal of the family, shame for the community, and a threat to the social order. In this context, the victim faces not only the violence inflicted on her body, but also the weight of an imagined guilt that, if she does not remain silent, she has betrayed the people who “love her the most.”

This silence learned in the family is later reproduced and reinforced by broader society through language, humor, and gender stereotypes. Violence is minimized and trivialized: “it was just a quarrel,” “it was jealousy,” “they had marital problems.” With such formulations, responsibility is systematically shifted from the perpetrator to the relationship, from patriarchal structures to individual “misunderstandings,” making violence appear as an emotional accident rather than a socially produced phenomenon.

In cases of femicide, this mechanism reaches its peak. Public discourse often focuses on the victim’s behavior: why did she not leave? Why did she go back? Why did she stay silent for so long? These questions are not innocent; they are forms of symbolic violence that shift blame and reaffirm the idea that survival is an individual responsibility, not a collective obligation. In this way, society not only fails to protect women, but also justifies the conditions that make violence possible.

Institutions that legitimize silence

On paper, North Macedonia has laws that recognize and condemn gender-based violence, but institutional practice often betrays them through inaction, delays, and the relativization of risk. Reporting violence is not necessarily accompanied by real protection, while bureaucratic procedures are slow, institutions are poorly coordinated, and responsibility often disappears amid unclear competencies. In this institutional vacuum, violence not only continues but becomes normalized.

When a woman reports violence and is not taken seriously, it signals that silence appears safer than reporting. When institutions minimize risk, they become part of the reproduction of violence. Protection orders that are not enforced, cases that are dragged out, and the lack of prosecution of perpetrators turn the law into a symbol without real power.

The situation becomes even more alarming due to the lack of concrete support mechanisms for women seeking help. In North Macedonia there are very few shelters for abused women, and existing capacities are limited, geographically unequal, and often dependent on short-term projects or civil society organizations. This means that for many women, especially outside urban centers, leaving violence is not a realistic option. Without safe housing, economic support, psychological counseling, and institutional protection, reporting violence becomes a risky act.

Institutional negligence is not neutral: it produces concrete, sometimes fatal, consequences. Every femicide following ignored reports shows that the state is not merely a spectator, but part of the chain that makes violence possible. Inaction is complicity.

Gender-based violence in North Macedonia does not survive because laws are lacking, but because silence has become the norm; in families, in society, and in institutions. Femicide is the most extreme form of this politics of silence, the predictable end that is tolerated, relativized, and systematically ignored. As long as violence is treated as a private matter rather than a collective failure, awareness will remain symbolic and victims will remain unprotected. Breaking the silence requires more than words and seasonal campaigns; it requires institutions that act, real protective mechanisms, and a society that accepts its responsibility before violence once again ends in murder.